Why rebates are a great consumer promotion

And we’re not talking about the mail-in rebates of yore. Digitized rebates have the potential to significantly increase sales while keeping profit margins wide.

The primary and most obvious difference between rebates and discounts is this: everybody gets a discount.

Only a percentage of consumers actually redeem rebates. And when not everyone redeems a rebate, you’ve sold many of your products at full price.

So at face value, common sense supports rebates as being better for a company’s bottom line than broadly applicable discounts.

Why rebates are often better than discounts

We analyzed more than a dozen studies and peer-reviewed articles on the topic so you don’t have to. And we learned that decades of research in behavioral economics points to rebates being the best consumer promotion for increasing sales and maximizing profit margins.

Granted, the vast majority of research we uncovered deals with mail-in rebates. Mail-in rebates are, naturally, more of a pain than digital rebates.

Consumers have to hold onto their receipt and rebate form, remember to fill it out, find envelopes, buy stamps, get in their car, drive to the post office – it’s a whole process.

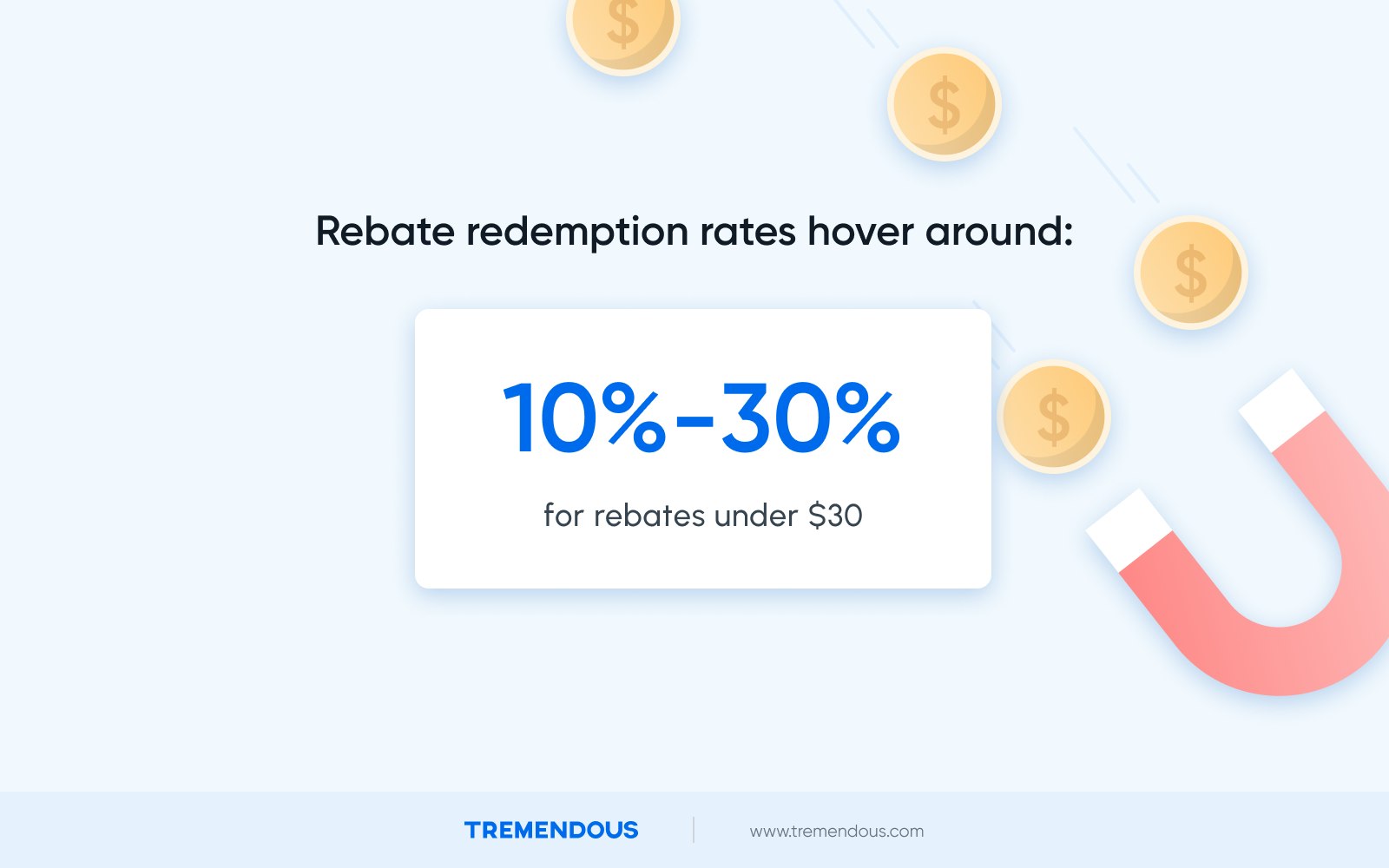

All this hassle keeps mail-in rebate redemption rates pretty low; redemption rates for rebates under $30 hover around 10%-30%, according to multiple sources.

Meanwhile, redemption rates for digital rebates are predictably higher, because filling in an online form is faster and easier.

Still, online rebate redemption rates are nowhere near 100%. And there’s a few reasons for that – hassle costs aren’t the only inhibiting factor that keep consumers from redeeming rebates.

People also fail to redeem rebates simply because they forget all about them. Forgetfulness alone cuts redemption rates by about 35% (Silk, 2004).

Learn more about the differences between rebates and discounts.

Why rebates work

Rebates are a payment that reduces the cost of a product or service at a later date. They’re great for B2C companies that want to increase sales of a product without discounting it.

To get the payment that makes the thing they bought cheaper, the customer has to do something. For mail-in rebates, this action generally involves mailing proof of purchase to the company.

Chen et al. offer a more considered explanation for why, exactly, rebates work in their 2004 paper on the topic.

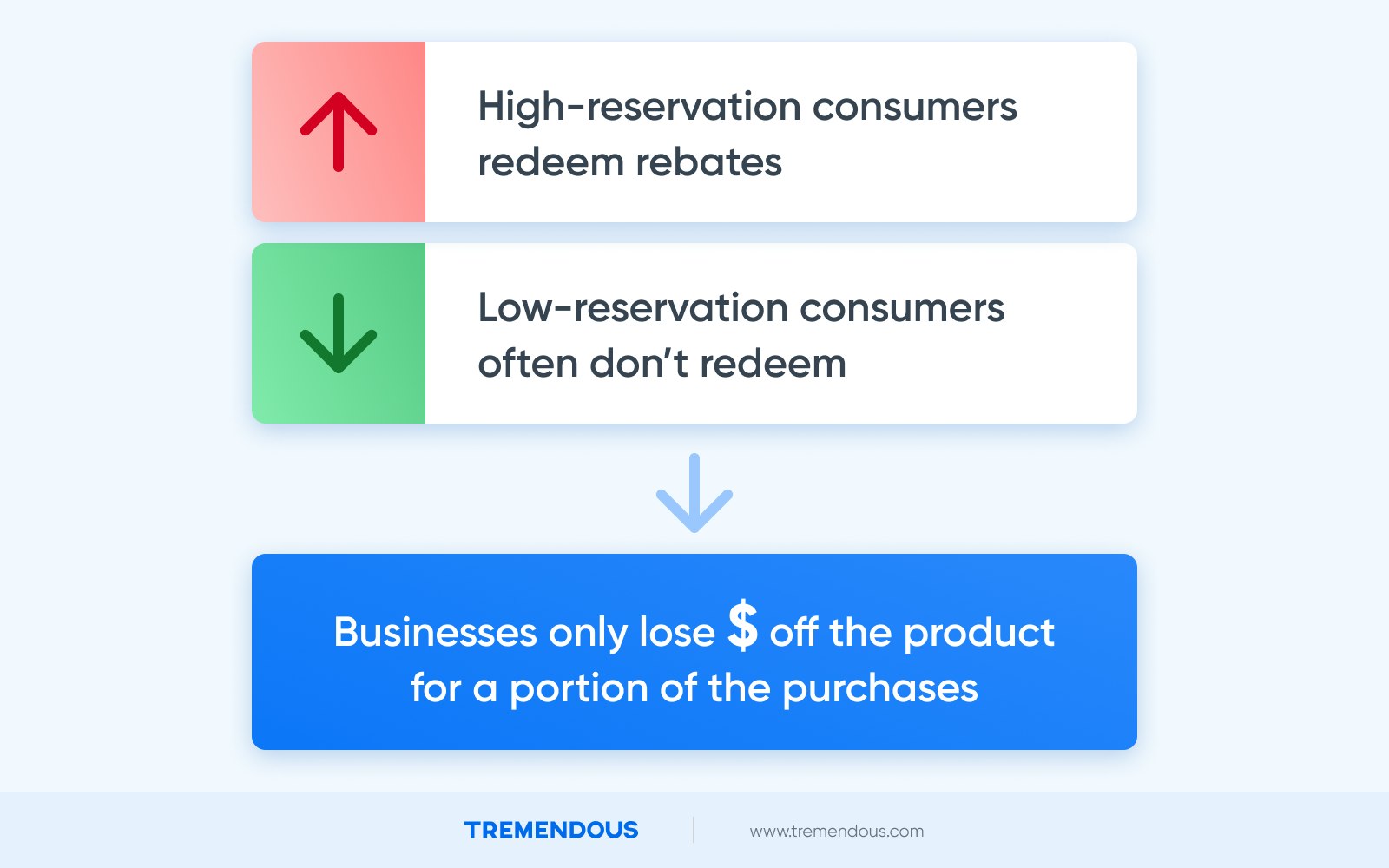

High-reservation price consumers are those who are especially price-conscious – they’re on the hunt for deals, and won’t make a purchase unless they know they’re getting a bargain.

Low-reservation price consumers aren’t too worried about price. They’d like a deal, like any of us, but they’re not making purchases solely based on whether they can get some cash back on it.

Rebates are a great way to attract both high- and low-reservation price consumers, while only taking dollars off the product for high-reservation consumers.

Look no further than your local state lottery for the psychological rationale behind why both high- and low-reservation price consumers like rebates.

Wishful thinking, a common bias where someone thinks an outcome is more likely than it is because they really want it, skews the consumer’s logic toward assuming they’ll follow through with a rebate even if the likelihood that they actually do is statistically slim (in the neighborhood of 10%-30% for rebates under $30).

This bias essentially turns us all into optimists when it comes to predicting our own behavior. We have trouble imagining outcomes that diverge from the best-case scenario.

But don’t discount discounts – they still have their benefits

Discounts are a lot more straightforward.

The discounted price is listed along with the item at the point of purchase, so the consumer pays less at checkout. Discounts can steer customers to one product versus another similar one.

Discounts employ the principle of urgency and the fear of missing out to motivate consumers to make a purchase (theoretically, in situations where they otherwise wouldn’t).

The thinking behind discounts is that consumers will worry that if they don’t buy now, they’ll miss out on a good deal.

In general, people are attracted to discounts that are visibly displayed beside original prices, compared to simply lower pricing.

For example, at a grocery store, consumers are more compelled by an orange sticker that says ‘You pay: $3.99’ overlaid on a price tag that says ‘$5.99, as opposed to a price tag that simply says $3.99.

They want to know what they’re getting away with. In this example, it’d be paying two less dollars.

When should you use discounts vs. rebates?

That depends on who your target consumer is.

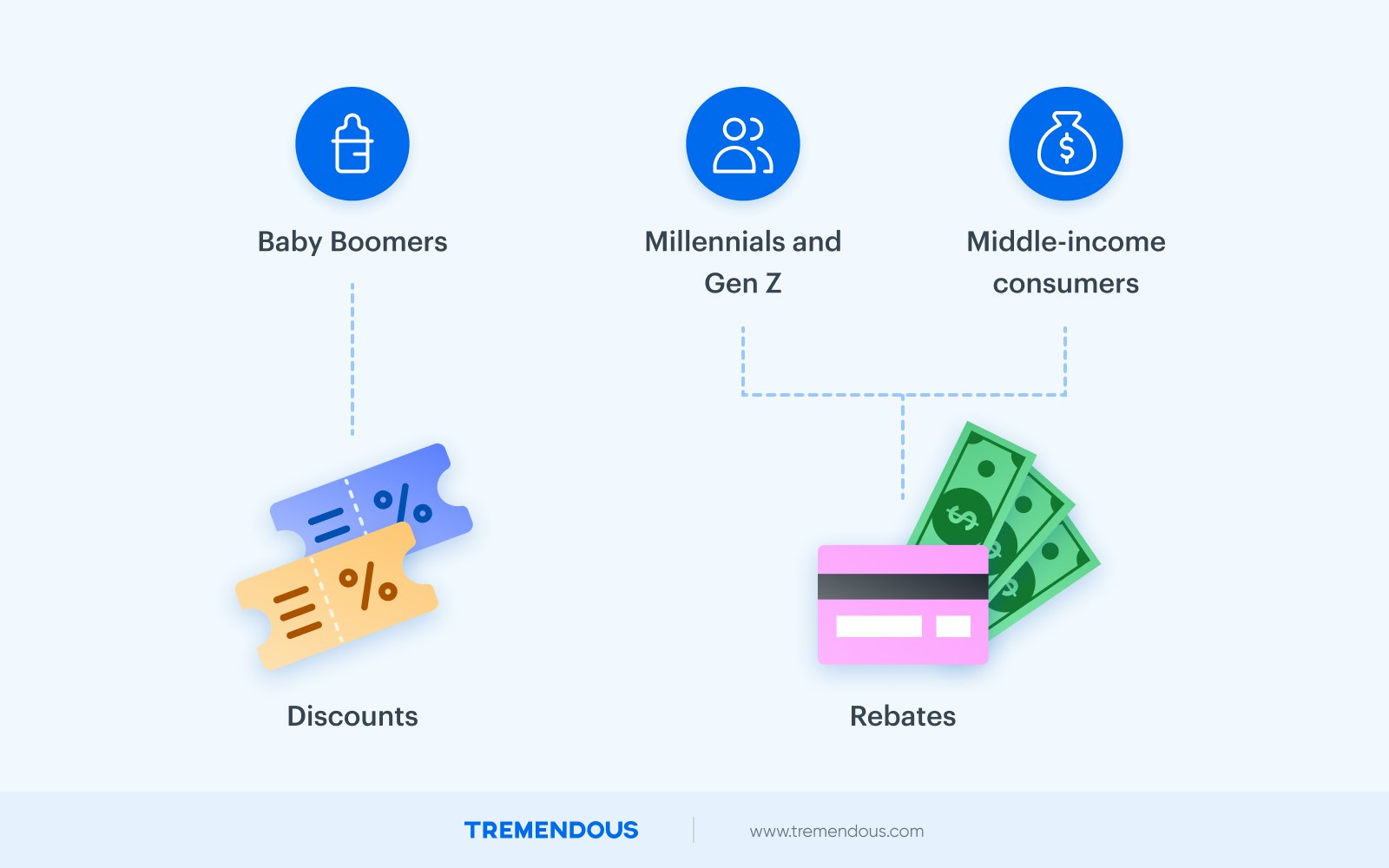

Baby Boomers: Go with discounts. Boomers are most likely to take advantage of discounts, such as coupons, with 96% of Americans older than 55 reporting that they use coupons. Seventy percent of Baby Boomers use paper coupons, 32% use online coupons, and 17% use mobile coupons.

Millennials and Gen Z : Go with rebates. Cashback offers (a kind of rebate) are especially attractive to Millenials and Gen Z. Seventy-four percent of Gen Z consumers say they spend more if they know they’ll get cash back, and 70% of millennials agree. Millennial moms in particular are 6% more likely than the general population to take advantage of 5% cash back offers.

Middle-income consumers: Also rebates.

Basically, middle-income consumers are more likely to see their budgets and cash flow fluctuate a bit from time to time.

Sometimes, they’ll be tight on cash. They’ll see an opportunity for a rebate and jump at the chance, confident that they’re motivated to get some money back.

But in a week, when it comes time to redeem the rebate, they might be feeling less stressed about money. Maybe getting that $10 or $20 back doesn’t seem like that big of a deal anymore.

They’ll forgo redeeming the rebate (because it’s too much effort, because they simply forgot, because they don’t feel like it) and end up paying full price for the item.

This fluctuation in marginal income utility creates the conditions for some middle-income consumers to follow through with redeeming rebates, and others not.

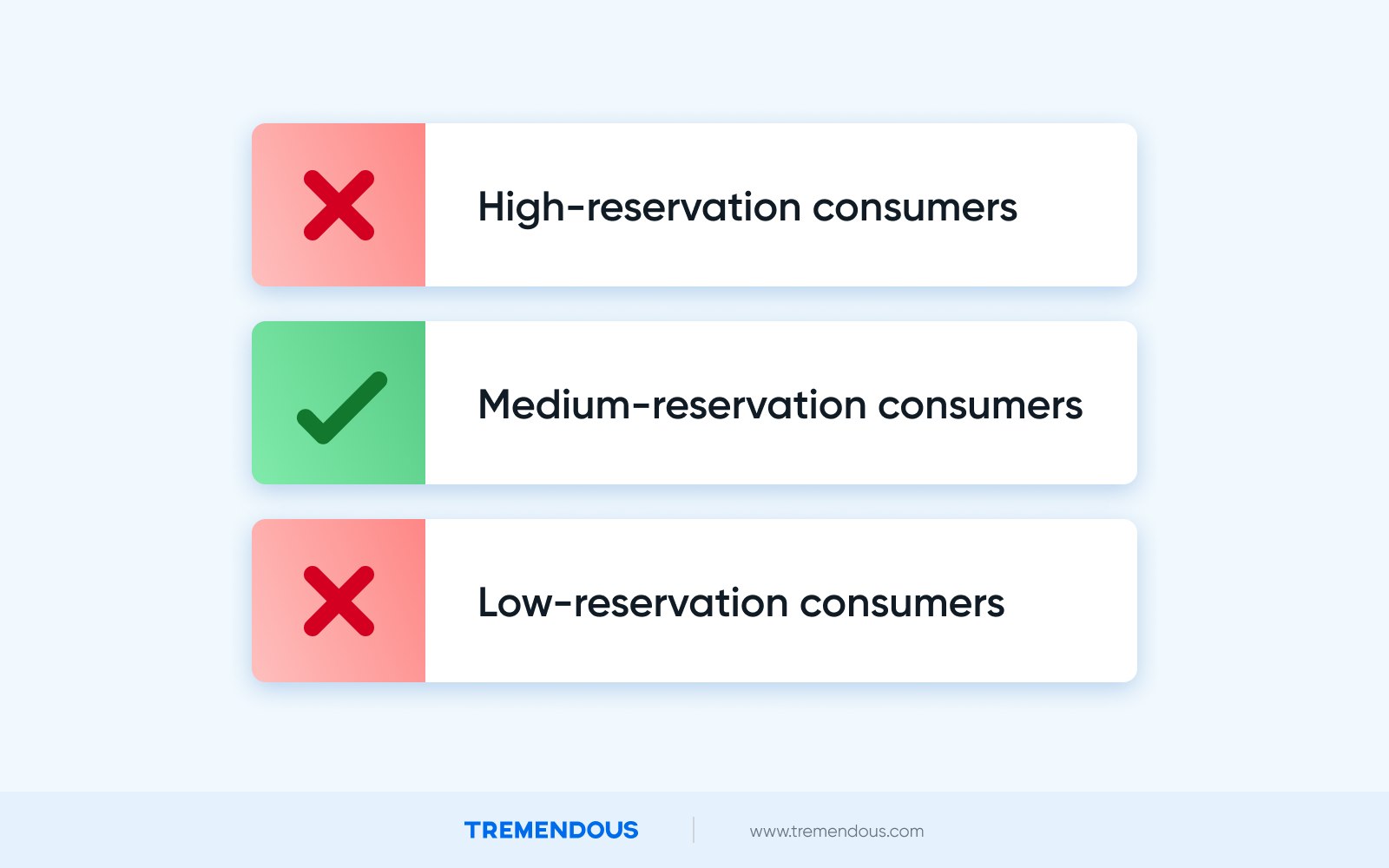

Conversely, high and low-income consumers aren’t great targets for rebates.

A couple dollars off a product doesn’t impact wealthy consumers too much. But it does make a difference for people with less disposable income.

So somebody with no budget is unlikely to spring for a rebate, because they don’t care about the savings.

Meanwhile, someone with a tight budget cares a lot, so they’re way more likely to actually submit the rebate. Good for them, less good for business.

The happy medium – the medium-income customer – is the best buyer to go for. They care about savings, but not enough that they’ll definitely go through with the rebate.

Their budget fluctuates. Maybe at the time of seeing the rebate offer, they were on a budget. But by the time they remember to redeem it, they’re feeling less money-conscious, and forgo submitting it.

Conclusion

The term ‘rebates’, itself, is pretty outdated. And it’s largely out of circulation in consumer-facing marketing and promotional copy.

In place of the word ‘rebates’, you’ll likely see phrases like “cashback”, or an offer for a free gift card with purchase.

Swapping the nomenclature with “cashback” makes it a little easier to notice that rebates are everywhere.

Retailers like Lowes, Best Buy, Macy’s, T-Mobile, and basically every bank and credit card company currently offer rebates, or cashback offers.

Discounts are still good, but you should consider adding a rebate program to your promotional mix.