How to minimize context switching at work

Skimming this article while you’re working on another project? Now you’re about 20% worse at both tasks. You’re context switching, or rapidly shifting your attention from one task to another, and it’s hurting your ability to do your best work.

People are talking about context switching a lot lately, even if they don’t realize it. Spotify recently generated a spate of LinkedIn buzz with its decision to slash all meetings from the company calendar that include more than 2 people.

This move, if effective, has the potential to increase worker productivity in two ways.

First, it removes the 30-60 minute interruption of an oft-needless meeting. Second, it eliminates the 23 minutes on either side of the meeting that people will spend attempting to refocus their attention on their next task.

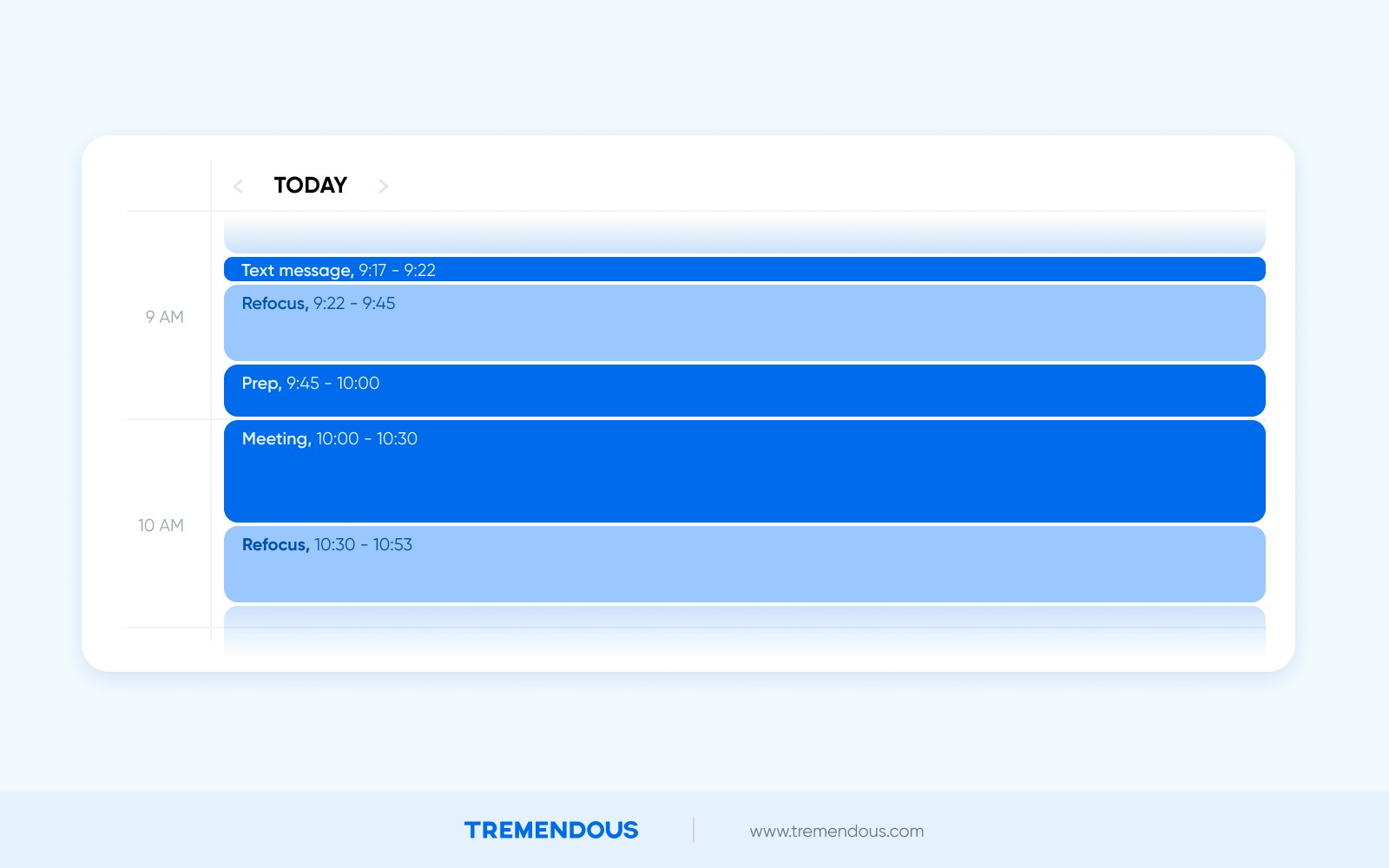

Twenty-three minutes per attention shift sounds like a lot. But according to one University of California Irvine study, that’s (on average) how long it takes people to recalibrate after a distraction, no matter how small.

It could be something as innocuous and cognitively-lightweight as a text message, or as dense as debugging a wall of code. No matter the heft or import of the distraction itself, it’ll cost you about 23 minutes in completely wasted time.

Cal Newport, who has written extensively on the topic, recently discussed the detriments of the digital workplace with New York Times reporter David Marchese.

At Tremendous, we have a fully remote work culture, so we’re completely reliant on digital means of communication, collaboration, and record-keeping.

This could be a minefield of distractions. We’re staring at our computers for the entire workday, fighting off the insidious beckoning of the internet, with its infinite open Chrome tabs and rabbit holes.

But there are some simple ways we get more out of our tech stacks by using them less frequently. And there are ways we structure our day to get a lot more high-quality work done.

Table of contents

The collaboration window

The most impactful way to get more done is by collaborating less.

Sounds counterintuitive, of course. And, in truth, we likely aren’t collaborating any less than the average worker. But we are collaborating less frequently.

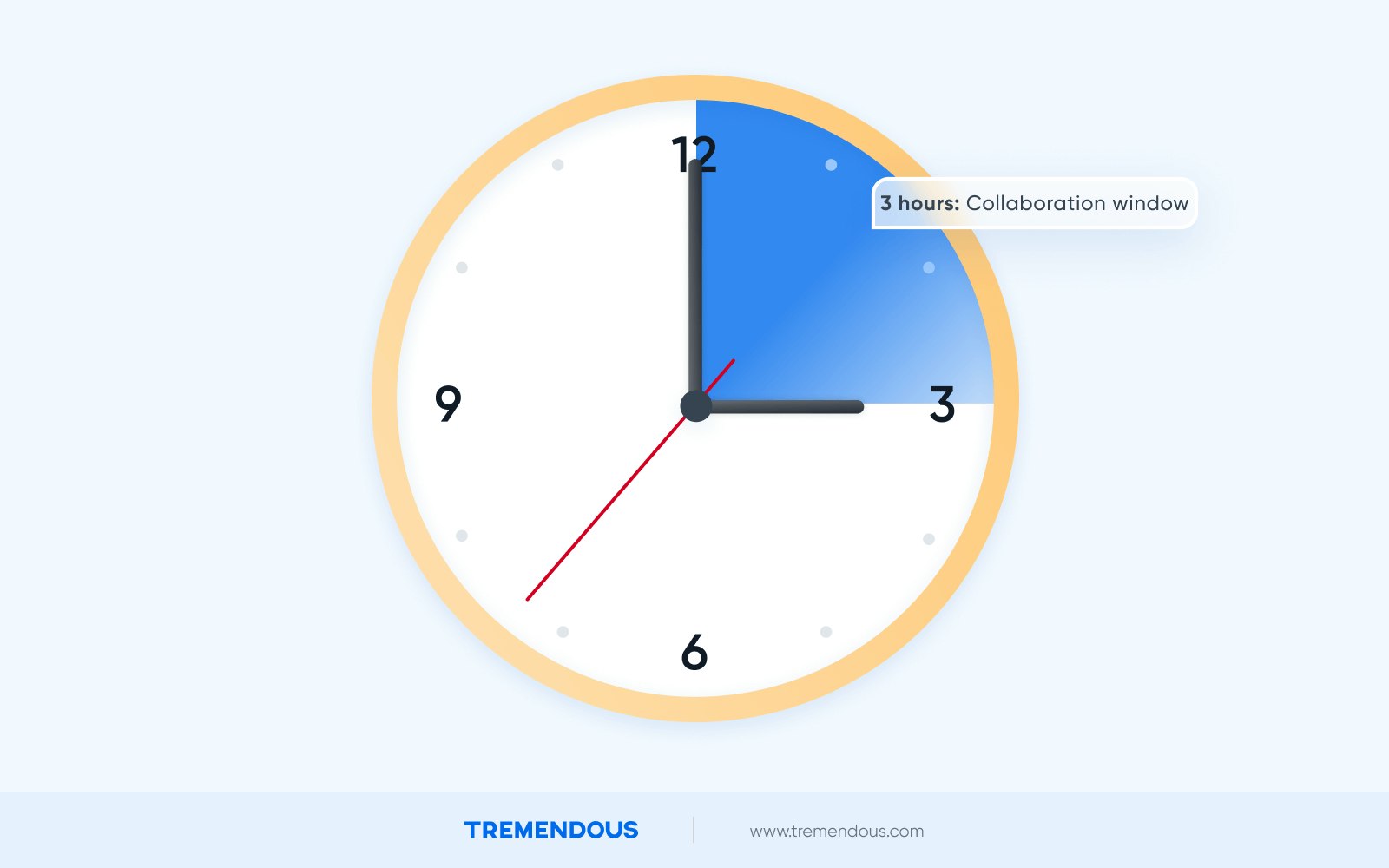

Rather than responding to each other in spurts and starts constantly throughout the day, we have an established 3-hour collaboration window.

Between the hours of 12pm-3pm Eastern time, all employees are generally expected to be online and responsive. (Of course, things come up, and that’s fine.)

This cordons off the hours on either side of the collaboration window for focus time. If we’re working 8 hour work days, we have the ability to devote 5 hours to focus time per day.

That’s enough time to get into a flow state, or achieve complete, uninterrupted immersion for a sustained period of time.

Each Slack ping, email notification, and text message shatters the delicate mental ecosystem required to support a flow state.

The collaboration window provides guardrails. We’re welcome to collaborate and distract each other from 12-3pm, but outside of that time period, we’re encouraged to go ghost.

While prescribing a collaboration window at your workplace is the first step in reducing distractions, the real work comes from getting buy-in across the organization.

Everyone, from executives to individual contributors, needs to understand the value of establishing a collaboration window.

Discussing the effects of context switching, the real cost of even brief distractions, and the benefits of flow states goes a long way towards maintaining the integrity of the collaboration window.

Meeting mindfulness

Canceling most meetings is only one piece of the puzzle when it comes to creating a successful async culture. But it is important. It not only reduces context switching, but it eliminates an excuse to multitask.

All of us sometimes sign into the meeting and half-listen while we do some work-related task on our other monitor.

One study from Carnegie Mellon University’s Human-Computer Interaction lab found that when you try to do two tasks at once, your performance on both tasks gets about 20 percent worse.

Basically, effective multitasking is impossible. And large meetings are a breeding ground for multitasking.

Especially large meetings over Zoom, where only one person can speak at a time and the rest are staring at their computers. Maybe you’re even reading this article right now while suffering through one such meeting.

Practicing meeting mindfulness doesn’t mean that we never hold meetings. We do. And we hold meetings of more than 2 people. We also have recurring meetings.

But we hold very, very few.

We use conversations on Slack, recorded Loom videos explaining concepts and initiatives, and briefs in Notion as replacements for meetings as often as possible.

We have a list of criteria that we use to determine whether we actually need to hold a meeting, or if a matter can be effectively settled asynchronously.

Apart from the stuff on this list, there are very few good reasons to ever schedule a meeting. We take these criteria seriously, and lean primarily on async communication to collaborate.

Default to public

Making as much of our communication and documentation public by default as possible also helps us reduce distractions.

When almost all information is publicly available, people ping each other less often.

So many nudges on Slack or email notifications come from people searching for information. When communication and documentation is public by default, people can find what they need themselves rather than disrupting someone else’s workflow to track it down.

Creating a culture that’s public by default means we do most collaboration in public Slack channels. Rather than private messaging one specific person, everyone is encouraged to work out problems and discuss ideas in pertinent channels.

If it’s a recommendation for a new marketing initiative, we drop the idea into our #team-marketing channel. If it’s a question or update related to the codebase, we drop it into #engineering.

While my impulse is generally to message my manager personally when I have an idea, I’ve trained myself to unlearn this behavior and instead turn to public content and marketing channels as the appropriate avenues for discussion.

In addition to communicating via public Slack channels, we also publish all briefs, proposals, and ongoing projects to our company Notion. Everyone at Tremendous can access our engineering docs, our sales briefs, our marketing initiative materials, et cetera.

Ensuring everyone has access to all information across the company doesn’t just help us reduce notifications.

It also makes the meetings we do have more pointed and brief. We can send each other updated docs to review ahead of meetings, so we don’t have to waste time silently reading documentation during the meeting or rehashing information that’s already written down.

Conclusion

The digital workplace is a very recent development when viewed within the context of historical timescales. That means, likely, we won’t have remote work down to a science for another few decades.

However, there are small ways we can optimize our interactions with the apps, tools, and communications platforms that make remote work possible.

Even though we’ve identified a few reliable methods for simplifying the remote workday, we’re still figuring it out ourselves. We’re continuously modifying our internal processes to make the most of our time and our tech stacks.