Always send research incentives: a guide

You should (almost) always offer research incentives in return for a participant’s time and feedback. It’s the right thing to do. Plus, incentives make research easier and better.

Incentives increase study response rates by up to 19% (Göritz, 2006).

They even have mild benefits to participant retention and response quality (Göritz and Luthe, 2013).

The most effective incentive is often money. But, not always.

“I am of the mindset that you should always pay [participant] for their time,” said Roberta Dombrowski, former head of UXR at User Interviews. “Because incentives actually encourage people to show up, and you're showing them that they're giving value.”

The gist

This is an introductory guide. We’ll tell you all about:

the role of incentives in research,

the various types of incentives and how they’re delivered,

ethical considerations, and

tax implications.

If you’re looking for information on how to build a research incentive program, stay tuned. Our guide to sending research incentives launches in August. It includes:

An incentive calculator

Guidance on incentive amounts

How to adjust strategies by research type, participant demographics, and other variables.

Until then, email me at ian@tremendous.com for specific questions, to subscribe to our newsletter, or to beta test our incentive calculator.

The role of incentives in research

Few people opt to participate in research on their own volition. Those that do, tend to be the squeaky wheel. Researchers use incentives (like money, physical gifts, or rhetorical appeals) to motivate those who wouldn’t normally participate.

And, incentives work.

Multiple reviews of dozens studies covering hundreds of thousands of participants proves that monetary (and other) incentives improve the process and outcomes of research (Göritz, 2006; Cantor, O’hare, and O’Conner, 2008; Singer and Ye, 2013).

“If you’re not compensating people for their feedback, one, they are a lot less likely to give you any in the first place. So you’re fighting to get it,” said Holly Cole, CEO of the Research Operations Community, two, the feedback that you do get is going to be lower quality, because free information is horribly biased.”

But incentives are just one of seven factors that influence response rate, according to professor Don Dillman in the book Survey Methodology (2020). To optimize for response rate and quality, you must:

Use various modes and methods to contact participants – by email, phone, snail mail or some other form of communication.

Leverage a better-known organization’s credibility – if the general public doesn’t know who you are, partner with a trusted brand name to provide social proof that your study is worth participating in.

Simplify and shorten your study – attention spans are short; cut your study to focus on the most salient information; chances are, more folks will participate (and finish) it.

Send research incentives – participants are giving you valuable feedback; compensate them for it.

Contact people multiple times – be strategic about how often and when you reach out; the cadence and frequency matter.

Explain the “why” – in all comms, explain the purpose of the survey, why the participant was selected, and other value-add details that prove the worthwhileness of your research.

Tailor tactics to your audience – meet people where they’re at; for instance, some populations may have less access to computers. Thus, mailed or telephone surveys are preferable.

Understanding the incentives in your arsenal

Research suggests a prepaid cash incentive is the most effective incentive for driving survey response rates ( Singer and Ye, 2013 ).

In reality, each study is different, and you should tailor your approach accordingly.

The best appeal will vary depending on your target population.

Participant populations will differ vastly by geography, culture, socioeconomics, and a variety of variables.

“In the U.S., $20 is lunch,” said Brad Orego, former head of research at Auth0. “But if you convert that $20 to local currencies in other parts of the world where we have customers, it’s a non-trivial amount.”

Monetary incentives are king

The industry was once reliant on checks, paper cash, and physical gift cards. The pandemic pushed many to adopt digital payment methods. That’s true of UXR, market research, academia, and clinical trials.

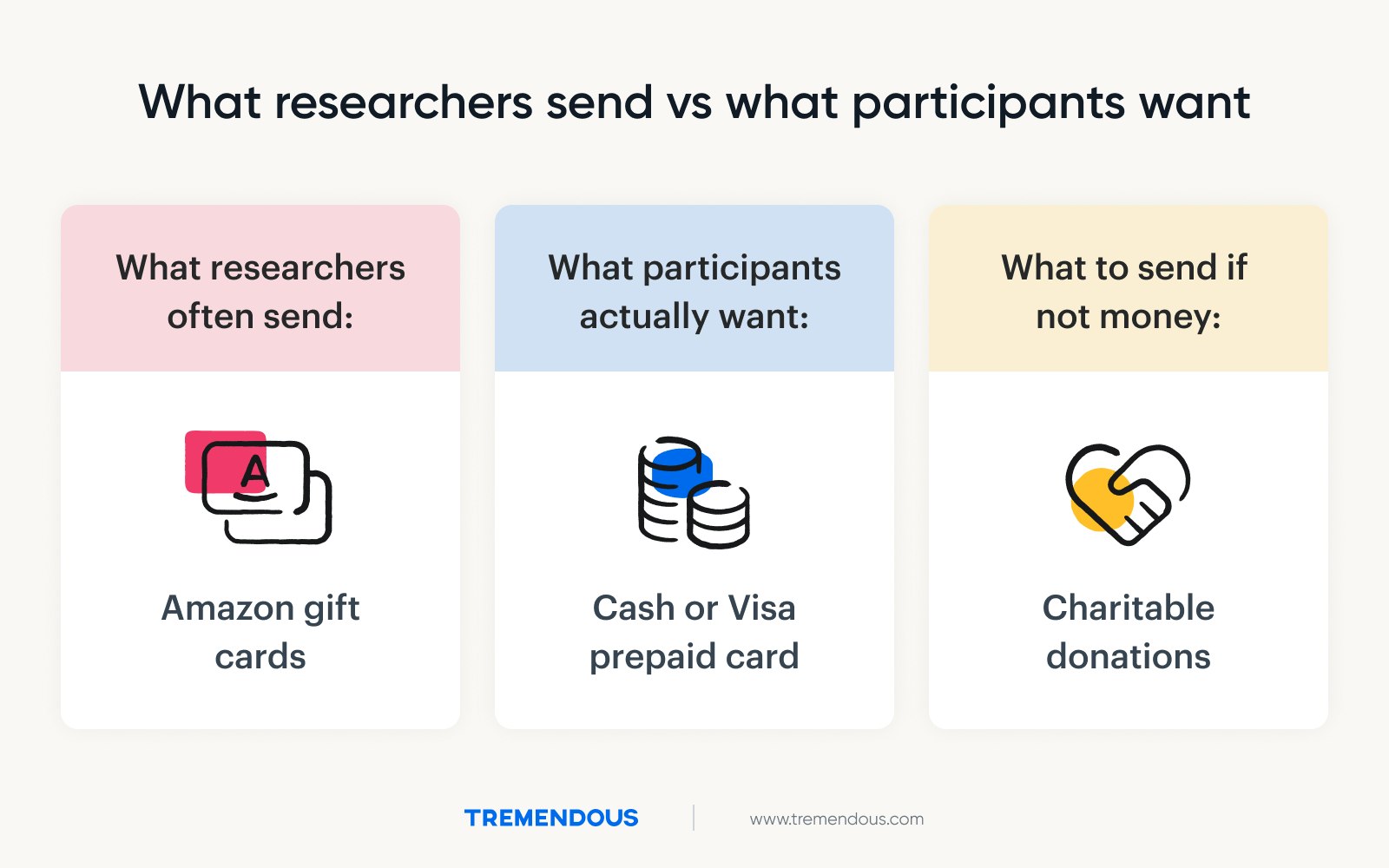

Researchers most often send Amazon.com Gift Cards. Tremendous conducted two surveys: one in 2022 of 368 Tremendous clients and a second in 2023 survey of 166 researchers. Both indicate an overwhelming use of Amazon.

We also conducted a conjoint analysis of recipient preference. If given a choice, recipients want a digital cash transfer or a Visa prepaid card over a gift card to a specific retailer.

Charitable donations are also a powerful research incentive. Often, recipients can’t accept incentives (or aren’t motivated by small dollar amounts). But a donation to a worthy cause might motivate.

“So many people disregard the fact that one in sixteen people in the United States works for the government,” Holly said. “You can’t pay them. But can you make a donation? Can you do volunteer days?”

Non-monetary incentives are equally important

Paying isn’t always appropriate, allowed, or within budget. Instead, try:

Piquing intellectual curiosity – explain to participants how they’re furthering a body of knowledge; perhaps provide early or free access to the findings.

Offering physical gifts – others are drawn to the materialistic: a sticker, a magnet, a tote bag, or some other swag. Perhaps an inexpensive electronic device. For small sample sizes, a personalized gift may be apt.

“We [did] in-person developer days in a handful of cities,” Brad said. “We’ll set up a booth for research, and the reward for participating is a custom button you can only get by participating at that event. It’s a scarcity play.”

When to deliver research incentives

A lot of research points to the effectiveness of sending a few dollars along with your initial outreach ( Cantor, O’hare, and O’Conner, 2008; Singer and Ye, 2013 ).

As the theory goes, giving someone money in advance makes them feel obligated to reciprocate — thus improving research participation rates.

Yet, research incentives are frequently paid upon completion or using an escrow system. Companies that run large panels also often employ points systems to encourage people to participate in multiple studies. Others couple a small prepaid incentive with a larger payment upon completion.

Research might say prepaying is the way to go. But, anecdotally, it’s not as common as you might expect. We suspect that’s due to the fear of handing over money without a guarantee of getting anything in return.

A chance to win

Lotteries or sweepstakes can be effective research incentives, particularly for the budget-constrained.

People are 18% more likely to participate in a study that offers a lottery versus one with no incentive (Göritz and Luthe (2013). For each increase in 10 EUR of prize size, the odds of participation rose by 2%

Emails that highlight a lottery in the subject line and body raised response rates by 5% (Zhang, Lonn, and Teasley (2016). That’s compared to emails that highlight the value of the survey itself.

Lotteries are ideal for tight budgets, as they turn incentives from a variable cost (dependent on sample size) to a fixed cost.

Ethics of research incentives

Incentives, particularly money, can influence behavior, and that introduces a variety of ethical considerations (Resnik, 2015).

Why incentives aren’t coercive

Monetary incentives can get people to make decisions and take risks that they wouldn’t otherwise do. But, this doesn’t meet the bar of coercion. It’s called something else.

“Coercion” has a strict definition, which details an “overt threat of harm” in order to gain compliance. Researchers tested this and concluded research incentives can never be coercive (Singer and Bossarte 2006).

But, incentives can enact “undue inducement.” Similar concept, minus overt harm.

If an incentive is too appealing, people can underestimate the research risks or overestimate the benefits (Resnik, 2015). For instance, if someone really needs money, they migh take on more risk than they otherwise would.

Exploitation of research participants

If offering too much money is ethically unsound, offering too little is exploitation.

Exploitation occurs when multiple parties agree to do something, but one side benefits disportionately.

Researchers point to pediatric research as an area prone to exploitation. A financial incentive might encourage parents to enroll their children in potentially risky research. This is exploitative because the parent disproportionately benefits, while the child assumes the risk.

Instead, parents should be reimbursed for travel and time, but “not so large that they distort parental judgment” (Resnik, 2015).

Biased enrollment in research

A net result of these ethical considerations is biased enrollment.

If certain populations are more motivated by an incentive, then your population will be skewed.

A sample that’s unrepresentative of the population impacts your ability to draw generalizations from the results.

Also, this can create a situation where people from a higher socioeconomic class conduct research on the lower classes. Thus, creating an exploitative bias in research.

Looking out for participants

Research has a dark history of subjecting human subjects to dangers in the name of advancing science and knowledge. Today, various guidelines and procedures safeguard participants.

A national fervor forced the U.S. government to act in 1970’s – in light of the Tuskegee Siphulus Experiements, among other ethically dubious human trials.

In 1974, the National Research Act was signed into law, creating a board of researchers to investigate the ethics of research.

Four years later, they released the Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research (which was later dubbed “The Belmont Report”).

The Belmont report outlined three ethical principles that remain:

Respect for persons – provide comprehensive information of the study’s risks and benefits, and get consent from participants.

Beneficence – or put simply "do no harm."

Justice – procedures are non-exploitative, and costs and benefits are distributed fairly and equally.

Since, these principles have been further investigated, refined and implemented in the form of:

Informed consent – researchers must provide participants a transparent and comprehensive accounting of the study, potential risks and expected benefits (Dickert et al., 2002). The participant must understand and consent to the terms.

Institutional review boards (IRBs) – these governing bodies oversee human-involved research for academic institutions, clinical trials, federal agencies, and other regulated industries

Adjusting incentive strategies depending on the audience – “Use of a variety of appeals (incentives) tailored to the needs of target populations offers the best hope for recruiting unbiased samples” (Singer and Bossarte 2006).

Reframing incentives

Researchers often take an extra step to guard against the perception of quid pro quo.

Many ditched the word “incentive” altogether.

Atlassian and Airtable both call them “thank-you gifts.”

The idea: a thank-you gift isn’t predicated on certain behaviors. It’s a show of appreciation for the participant’s time and feedback.

“We don’t want to think of it as compensation, or an incentive exchange,” said Adele Wallrich, research operations manager at Airtable. “We want to make it about gratitude, and fostering that relationship with users.”

The $600 tax threshold

Research incentives are taxable income. Doesn’t matter if it’s cash, a gift card, or anything of monetary value.

Recipients must report income to the IRS when they receives $600 or more in a calendar year from the same company.

Before tax season, you should request a W-9 (“Request for Taxpayer Identification Number and Certification”) from the participant.

During tax season, file a 1099-MISC (“Miscellaneous Income”) along with your other tax paperwork, just as you would do when hiring a freelancer or contract worker.

Always consult an attorney for tax advice.

If individual participants partake in multiple studies, it’s particularly important to track incentive spend, and ask for the necessary forms in advance.

“It’s uncomfortable to have to reach out after the fact and be like, “Hey, you participated in this thing with us, we need you to fill out this 1099,” Adele said. “You want to avoid that, and remain compliant. Because why would you want to mess with the IRS? There’s no point”

The takeaway

Incentives play a vital role in research, driving participation rates and likely improving response quality. Cash (or an equivalent) is usually the best incentive, but different populations are motivated by different things.

So, be flexible. Understand the ethical considerations and tax implications. Above all else, just find a way to show participants you appreciate their time and feedback.

The easiest possible way to send incentives is by using Tremendous. We're the simplest way to send people money, no matter where in the world they are.